Saving Wildlife Habitat at the Edge of the San Francisco Bay

A donation from Cargill launches America’s largest tidal wetland restoration project along the California coast.

January 01, 2015

When government officials, environmentalists and Warren Staley, Cargill’s chairman and chief executive officer, gathered at the edge of the San Francisco Bay in 2002, they were celebrating something big. It was the official launch of one of the most ambitious wetlands restoration programs in US history. Together with its partners, Cargill would help restore one of the most important ecosystems on the Pacific Flyway, a route for migratory birds extending from Alaska to Patagonia.

Salt has been produced at the edge of the San Francisco Bay for more than 150 years. In the late 1990s, after operating its salt processing site for more than 30 years, Cargill determined that it could re-engineer its operations to produce all the salt it needed on a third of its acreage. With this commitment and a capital investment, Cargill would make it possible to transform the natural environment of San Francisco Bay by greatly increasing tidal marsh and related habitat for the area’s wildlife.

State and federal agencies were eager to accept land ownership from Cargill. But when an appraisal team, directed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the California Wildlife Conservation Board, determined the value of Cargill’s land at more than US $243 million, hopes dimmed among environmentalists and lawmakers, as it seemed increasingly unlikely that they could assemble the resources to buy the property.

The turning point came in the early 2000s when Staley agreed to work with US Senator Dianne Feinstein to bring the price within reach. Working with Cargill Vice President Bill Britt, who had played a key role in coordinating similar land transfers in the past, the parties reached a resolution that would significantly benefit the environment without affecting Cargill’s salt business in California. The company would donate more than half of the value of the land—15,100 acres in the South Bay and 1,400 acres in the North Bay—a generous 16,500 acres in total that contained 25 square miles of salt ponds and other property.

“We have been able to contribute to these important environmental goals without sacrificing the vitality of our business.”

— Warren Staley, Chief Executive Officer of Cargill

Thanks to the innovative plan, Cargill would be able to continue harvesting and refining more than 500,000 tons of high-quality salt each year, but on far less land. Cargill employees worked with agency officials to reconnect the salt ponds to the bay. New tidal patterns began to convert the salt ponds to tidal wetlands: sediments accumulated, and slowly, native vegetation began to grow back. Millions of birds and other wildlife found a new home amongst the salt ponds, mudflats, and tidal and seasonal wetlands. Altogether, it created a network of thriving natural habitats for local and migratory wildlife.

This is just one of the Bay Area properties that Cargill has transferred to public ownership, helping to launch one of the largest wetlands restoration efforts in the country.

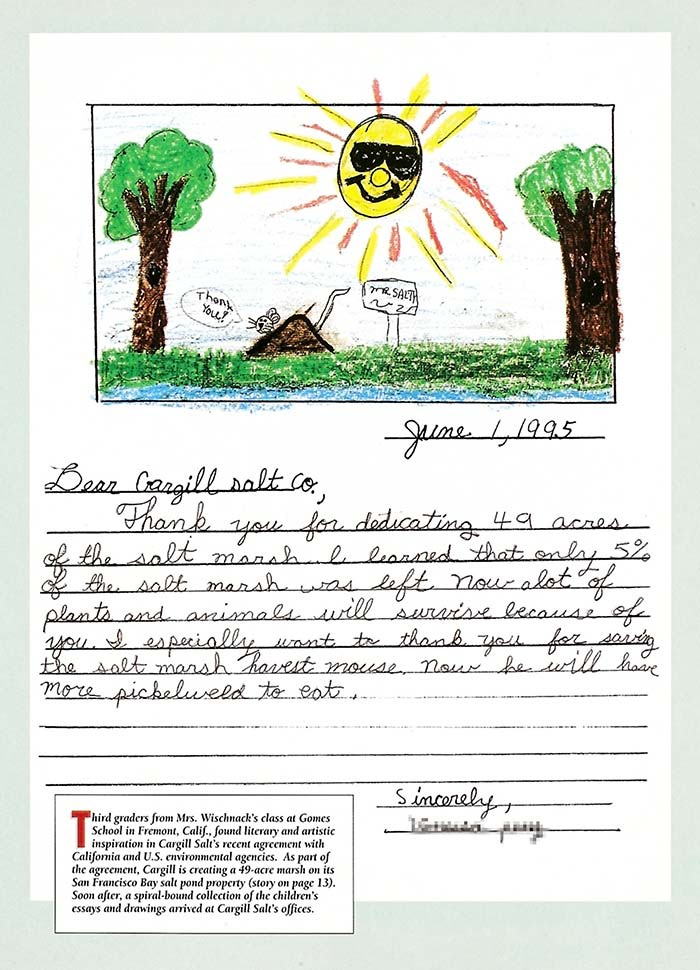

[image caption] Environmental education is a key component of the San Francisco Bay project. Here, a third-grade student writes to Cargill, thanking the company for its efforts.

[image caption] Environmental education is a key component of the San Francisco Bay project. Here, a third-grade student writes to Cargill, thanking the company for its efforts.