A Glimpse into the History of Hedging

Go ahead, Google “hedging” or “financial hedging”—see what comes up on that first page.

Most likely you’ll find a vast list of articles that include technical terms or definitions of what hedging is and the role it plays in the finance world.

If you are part of the 95-plus-percent of the world not using this term on a daily basis– but are curious about learning or understanding it in a simple way– you will most likely end up more confused than you were before you started searching.

Hedging, as a financial concept, has always been confusing.

We often hear at meetings and events around the world: “What is hedging, anyway?” It’s a common question—still, in 2017. Today I’d like to attempt to explain the concept of “hedging” in terms you can easily understand. Let’s start by talking about a little history. Specifically, the history of modern trading, which should explain why hedging started in the first place.

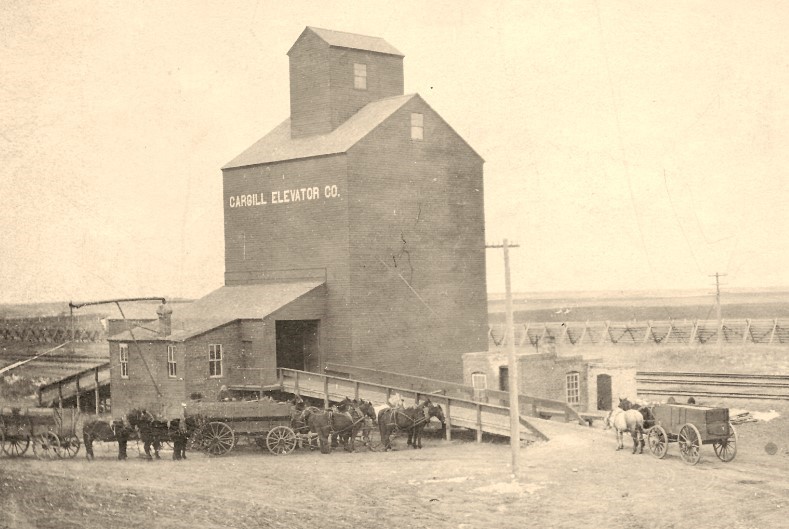

The most recent accounts of “hedging” occurred in the mid-1800s, even though there is historical evidence that attempts to “hedge” happened well before. In the mid-1800s, Chicago became a commercial center of industry, a focal point where people from across the Midwest came together from a network of rail lines. Farmers were selling grain to buyers who would then ship their grain all over the U.S.

Farmers would produce grain during the spring and summer, and come to the center of trade (Chicago) at the end of the summer to sell it. More often than not, a number of dealers would then offer a price to secure those purchases for a limited amount of grain.

The amount of grain produced by farmers did not necessarily align with dealer demand. There were fewer dealers than farmers, and they often wanted to buy a lesser quantity of grain than what farmers were ready to offer, creating a race to the bottom in terms of pricing.

After selling grain in this “market”, whatever quantity farmers didn’t sell or consume for their own animal-feeding needs through the winter until the next crop, would ultimately be wasted. This cycle forced many farmers and some dealers into financial hardship, with countless stories of debts not being paid and banks seizing farms.

Producing grain in advance, without any assurances of what price the grain could sell for, did not provide any level of certainty to farmers. They couldn’t plan for how much grain to produce, how much margin they could expect or how to resource their farms.

Then, around 1848, farmers and dealers came up with a better idea. Farmers would ask dealers if they were willing to commit to buy grain at a specific, agreed-upon price today to be paid in the future when the grain was delivered (often in the next year).

If the farmer and the dealer agreed, the two parties made a “commitment” they would write on a blackboard that would hold both liable: for the farmer to deliver the grain at the specified price, and for the dealer to buy the grain at the same specified price.

Why was this "commitment" so fundamentally important?

These “commitments” allowed farmers to plan production for next year’s crops. Knowing exact prices for how much grain they would sell allowed farmers to secure monetary gains, and as a result, they could reverse engineer how much to invest in the next crop season.

The new process also allowed dealers to secure production and prices they could turn around for budget purposes and monetary gains, and to fulfill the required supplies for their businesses.

Finally, these “commitments” also created better equilibrium for supply and demand to balance and reduced waste and financial hardship, bringing stability to the overall system.

These events essentially summarize the beginning of the Chicago Board of Trade, which was founded in 1848. It also represents the origins of modern hedging in the United States.

In addition to the Chicago Board of Trade, other exchanges developed concepts for similar needs with other commodity groups. For example, the London Metals Exchange originated in the U.K. to trade copper that originated in Chile and traded in London to fulfill demand.

From there, the concept of hedging and commitment evolved in global exchanges to perfect, improve and preserve the commitment integrity. Some aspects of how it has been perfected involve defining standard qualities of the accepted commodity, the credit requirements for buyers and sellers to be accepted, and regulation.

This all leads to a simple, modern-day definition of hedging: A future financial commitment to buy or sell a defined quantity of an asset class at a determined price, so an entity can insure or protect what needs to be produced, consumed or invested in.

What does hedging look like now?

How is hedging used today? What kinds of companies and industries use hedging techniques? What does it look like?

All great questions, and they would best be answered by outlining a few examples from different industries and companies:

- Farmers and dealers still hedge grain on a daily basis. Other farmers and dealers hedge coffee, cocoa, sugar, orange juice, rice, rubber, and oils in similar exchanges across the world.

- An oil producer may insure the price of a barrel of oil so they can invest in extracting oil from the ground, and ensure a financial institution can help finance the operation when margins are insured.

- An airline may need to insure the jet fuel needed for the airfares already sold at a fixed price for the next three months.

- A soda bottler may need to buy aluminum in a futures market to insure the price of the cans they are about to buy in the next 12 months.

- A cheese factory may need to insure the price of milk that will be used as raw material for the mozzarella that will be manufactured in the next few months.

These materials have been prepared by personnel in the Sales and Trading Departments of Cargill Risk Management, a business unit of Cargill, Incorporated based on publicly available sources, and is not the product of any Research Department. These materials are not research reports and are not intended as such. These materials are for the general information of our customers and are a “solicitation” only as that term is used within CFTC Rules 1.71 and 23.605, as promulgated under the U.S. Commodity Exchange Act. These materials are provided for informational purposes only and are not otherwise intended as an offer to sell, or the solicitation of an offer to purchase, any swap, security or other financial instrument. These materials contain preliminary information that is subject to change and that is not intended to be complete or to constitute all of the information necessary to evaluate the consequences of entering into a swap transaction and/ or investing in any securities or other financial instruments described herein. These materials also include information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but Cargill Risk Management does not warrant their completeness or accuracy. In no event shall Cargill Risk Management be liable for any use by any party of, for any decision made or action taken by any party in reliance upon, or for any inaccuracies or errors in, or omissions from, the information contained in these materials and such information may not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of participating in any transaction. All projections, forecasts and estimates of returns and other “forward-looking” information not purely historical in nature are based on assumptions, which are unlikely to be consistent with, and may differ materially from, actual events or conditions. Such forward-looking information only illustrates hypothetical results under certain assumptions. Actual results will vary, and the variations may be material. Nothing herein should be construed as an investment recommendation or as legal, tax, investment or accounting advice. Cargill Risk Management is a provisionally registered Swap Dealer and operates under “Order of Limited Purpose Designations for Cargill, Incorporated and an Affiliate.”